|

Doctoral Student's Dissertation Examines Americans' Fascination

With Professional Wrestling

By Cathy Keen |

MANIA! |

The nation’s infatuation with professional wrestling now borders on a mania fueled by alienation from everyday life, not the love of athletic "competition" within the ring, says a recent University of Florida doctoral graduate who researched the unconventional topic for his dissertation in anthropology.

Like a passion

play, wrestling productions are symbolic reenactments of the audience’s

personal and social struggles, says Aaron Feigenbaum, whose provocative

analysis ultimately helped him land a job with the World Wrestling Federation.

Like a passion

play, wrestling productions are symbolic reenactments of the audience’s

personal and social struggles, says Aaron Feigenbaum, whose provocative

analysis ultimately helped him land a job with the World Wrestling Federation.

"Wrestling superstars do not engage in heroic contests against the Gods or in epic quests for immortality," Feigenbaum says. "They engage in battles against tyrannical employers, moral crusaders, hypocritical power brokers and a social system that threatens their freedom and leaves them alienated from their fellow human beings."

With 40 million television viewers each week, six of the top 10 programs

on cable television are either WWF or World Championship Wrestling productions,

including WWF’s "Raw Is War," the highest-rated show.

Viewers may witness anything from a wrestler driving a hearse into the arena and threatening to take another superstar’s soul to 20,000 fans cheering for a sock. They may hear a crowd of spectators shout in unison about venturing to strange places such as "Jabroni Drive" and the "Smackdown Hotel." Or they may see a wrestler crawl under the ring in the middle of a match and emerge with a crate of bananas that will ultimately be smashed over his opponent’s head. There are even fireworks — and scary creatures.

With all the drama of theater, the suspense of a sporting event, the issues of a political debate and the special effects of a rock concert, professional wrestling productions combine just about every form of American popular culture into one glorious spectacle that has come to be known as "sports entertainment," Feigenbaum says.

"Seinfield, the most popular television sitcom of the 1990s is often referred to as ‘the show about nothing,’" he says. "In contrast, sports entertainment may be considered ‘the show about everything.’

"For those who want action, there is action," Feigenbaum explains. "For those who want to see scantily clad males or females, there are scantily clad males or females. For those who want political satire, there is plenty of it. And for those who wish they could punch their boss, sports entertainment can provide that as well."

Despite all the glitz and glamour surrounding wrestling productions, the performances spotlight the personal conflicts of its audience, with the battles in the story lines reflecting the social experience, he says.

"Aaron has approached the study of wrestling not as a sport, but as a ritual drama that’s very similar to plays, soap operas, religious ceremonies and things of that sort," says John Moore, a UF anthropology professor and the chairman of Feigenbaum’s dissertation committee. "The point is to act out in a ritual manner the important values and relationships in contemporary American society."

Rituals let people break free from everyday roles and create new ones, as well as reconfigure the existing social order to make sense of their world, Feigenbaum explains in his dissertation.

"It would have been possible to write a silly, trivial dissertation

about wrestling," Moore says. "But what Aaron did was to test some very

serious and some very traditional ideas of culture within the venue of

wrestling."

Feigenbaum combined a variety of study methods in his research. He interviewed a representative sample of the wrestling audience, analyzed tapes of televised events, attended live wrestling performances, studied sports entertainment Internet sites and interviewed key individuals in the business, including WWF Chairman Vince McMahon Jr.

Some people initially dismissed Feigenbaum’s dissertation topic as frivolous, Moore recalls, because they didn't understand the nature of wrestling, thinking it was built around a contest to see who would win.

"They naively believed it was more like boxing, when everyone involved

with it realizes that it is more like Kabuki theater," Moore says.

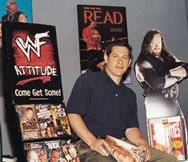

Through his job at World Wrestling Federation Entertainment, Aaron Feigenbaum gets to attend numerous WWF events and write about professional wrestlers for such WWF publications as WWF Magazine and Raw. |

Disapproval disappeared once the 34-year-old Feigenbaum, a lifetime

wrestling fan from Chevy Chase, Md., was hired by the WWF after he graduated

in May, Moore says.

Actually, Feigenbaum’s career move outside the conventional path of university teaching is not that unusual. UF has the largest department of applied anthropology in the world, according to Moore, with Ph.D. graduates more likely to go to work for such organizations as the World Bank and United Nations than to take positions in academia. Feigenbaum came to the WWF’s attention when he telephoned with questions for his dissertation research. Laura Bryson, currently managing editor of WWF Magazine, who took his call and helped him get an interview with McMahon, says Feigenbaum was the first person she thought of when she had a job opening for a writer. |

Besides being able to write his dissertation in lay language, Feigenbaum showed a sophisticated grasp of the genre as a forum for people to unleash their pent-up frustrations with society, says Bryson, who also has a degree in anthropology.

"When the classic struggle is waged between Vince McMahon and Stone Cold Steve Austin," she says, "Vince represents the Machiavellian capitalist who works his workers to the bone not caring about their welfare, while Stone Cold Austin represents hard-working people who will bust their tails to put food on the table. Aaron understands this."

Superstars, who come to depict the audience in its fight against perpetrators of injustice, become heroes, Feigenbaum writes in his dissertation. Their battles are the audience’s battles and their victories, the audience’s victories.

Chyna, a female wrestler who competes against males, personifies women trying to make it in a man’s world, Feigenbaum says. The harassment she endures and the obstacles she must overcome mimic the real-life experiences of many female viewers, who make up 30 to 50 percent of all wrestling fans.

D-Generation X, a group of rebellious superstars, typifies young adults revolting against authority, while the Corporation’s entrance theme is the rallying cry for those who enjoy abusing power or would like to do so, he says.

In mimicking the real-life experiences of its audience, professional wrestling stories also reflect the politics of the day, from the all-American types of the 1920s to today’s cold-hearted corporate bosses, Feigenbaum says. The "bad guys" in the ring embodied the Germans and Japanese during World War II, the Soviets from the ‘50s through the ‘80s and the Iranians during the hostage crisis of the late ‘70s and early ‘80s, he says.

"With no foreign enemies to channel aggression toward after the Cold War ended, the focus turned inward to injustices in American society," Feigenbaum says. "Bad guys were either big corporate types who try to control people or moral crusaders who demean the audience’s taste."

The United States has become a land of extravagant expectations, but few products or experiences can come close to satisfying these, Feigenbaum says. So consumers buy more products, travel to new places and try different experiences, he says.

"Then along comes sports entertainment, the great American pastime that has evolved into a spectacle of everything and anything, a one-stop marketplace that can take care of all of our entertainment needs," he says.

What distinguishes professional wrestling from other sporting events is not necessarily the stories that are told or the symbolism of the performers, but the interaction between the fans and performers, Feigenbaum says. The audience can be rude, obnoxious and silly in expressing its love or outrage for a story’s characters, he says.

Wrestling fans are stereotyped as blue-collar and uneducated, but a recent survey by Frank Ashley, a professor of sports management at Texas A&M University, found that more than 40 percent of the audience at a WCW show in College Station, Texas, had annual incomes of at least $40,000 and 62 percent had attended college or earned a college degree.

Sports entertainment fans form a relatively tight community, Feigenbaum says. The never-ending abuse heaped upon them for liking the activity serves both as a metaphor for the alienation they experience in everyday life and a rallying cry around which to build their community, he says.

Not surprisingly, when a group of people are continually demeaned, it strengthens their resolve not to open up to outsiders, he says.

But

being a good ethnographer is an essential skill of an anthropologist, and

Feigenbaum believes his laid-back and easygoing manner helped him develop

rapport with wrestling fans.

But

being a good ethnographer is an essential skill of an anthropologist, and

Feigenbaum believes his laid-back and easygoing manner helped him develop

rapport with wrestling fans.

The popular tendency to label sports entertainment as "lowbrow entertainment" is something anthropologists strive to avoid, Feigenbaum says. Part of what the concept of "cultural relativism" in the field is all about is learning to respect different people’s ways of doing things, he says.

"It also helped me that informants trusted me, not only because I was a fan, but also because I took a little abuse," Feigenbaum says. While working on his dissertation, one person went so far as to ask if he was writing it in crayon.

Today, the reception to how he earns his living is more mixed. "I usually get one of two reactions," he says. "I either get the scoffs or I get people who say ‘I think it’s the coolest thing in the world.’"

Feigenbaum says he still views sports entertainment from an academic perspective, even though he knows more about what goes on behind the scenes. To gather material for his stories, he gets to meet wrestling stars who in the past he would have been able to see only at shows or on television.

"A lot of these guys are huge, a lot of the women are very glamorous," he says. " No one has picked me up and body slammed me. I’m too new. But maybe they will once I’ve been here a little longer."

Even though anger and alienation lie at the heart of sports entertainment, the experience is meant to be fun and entertaining. Audiences can cheer their heroes, jeer their villains and, most of all, celebrate their victories, he says.

"It gives fans an opportunity to laugh, to cry, to celebrate, to revolt, to come together with others and to break free from everyone," he says. "It provides everything and anything for a society that expects everything and anything."

Aaron Feigenbaum

aaron.feigenbaum@wwfent.com