|

|

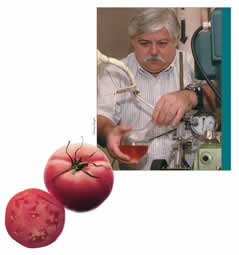

Blemished Tomatoes Source Of Antioxidant Lycopenedownloadable pdfResearchers at the University of Florida have found an inexpensive way to extract the antioxidant lycopene from tomatoes, a technology that could turn a mountain of discarded produce into a marketable commodity. "It's a very good solution to two problems," said Murat Balaban, a professor of food engineering and processing at UF's Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. "You have a shortage of lycopene, which costs $2,500 per kilo in its pure form. And you have farmers with tons of blemished tomatoes that they can't sell or even give away."

Balaban is part of a team of six UF researchers who are investigating new lycopene extraction methods. The team is headed by Amy Simonne, an assistant professor of food safety and quality at UF. Lycopene, the substance that gives tomatoes their characteristic red color, is also a powerful antioxidant, one of a family of chemicals that promote health by protecting cells from damage caused by oxidation. Pure lycopene has traditionally been extracted from tomatoes through a process using chemical solvents - Even so, there's no shortage of raw material for the fledgling lycopene industry. Every year, packing and processing plants throw away about one out of every 10 tomatoes brought in by farmers, UF and industry experts say. With Americans consuming more than 25 billion pounds of tomatoes a year, according to U.S. Department o Agriculture statistics, those cast-off tomatoes add up to a mountain of produce. The discarded fruit typically isn't in very bad condition, but even minor cosmetic problems - such as blemishes or an odd shape - can keep a tomato from meeting USDA quality standards. For packers, those tomatoes are worse than worthless. Packing houses must foot the bill for disposal of the tomatoes, which is governed by federal rules meant to prevent runoff of the fruit's acidic juices. With luck, a packing house can find farmers willing to take away at least some of the discards for use as cattle feed. But Balaban and his colleagues may have solved that problem. By putting tomatoes in a supercritical gas extractor - like the machine used to decaffeinate coffee beans - they can remove a few grams of expensive lycopene from a few hundred pounds of cast-off produce. "Any new use for these tomatoes would be of tremendous value to us," said Jay Taylor, president of Taylor and Fulton, a packing house in Palmetto. "It's sad to see this much food going to waste, particularly when so many of these tomatoes have only minor problems." Murat Balaban, MOBalaban@ifas.ufl.edu by Tim Lockette

|