UF Doctoral Student Keith Akins Spent Three Years In Florida Militia Groups Seeking A Better Understanding of What Motivated Their Members

By Joseph Kays

Like most Americans, Keith

Akins

was horrified by the images of the dead and injured being carried out of

the ruins of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City on

April 19, 1995.

Like most Americans, Keith

Akins

was horrified by the images of the dead and injured being carried out of

the ruins of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City on

April 19, 1995.

And when it turned out that Timothy McVeigh, one of the men convicted of planting the massive truck bomb that destroyed the building and killed 168 people, was a decorated veteran of the Gulf War, Akins couldn't help but wonder what drove him to commit this horrific act.

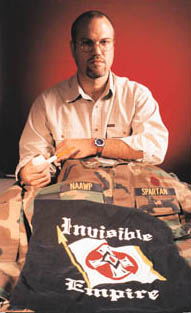

As a disabled veteran himself, Akins struggled to understand the influence the Militia Movement had on McVeigh. So, for his doctoral dissertation in anthropology, Akins decided to find out firsthand about the movement. Akins joined and spent three years as an active member of various militia groups in Florida, organizing rallies, planning meetings and training sessions. He also joined a skinhead group and a Ku Klux Klan chapter.

"I hated what these people stood for, but as I got to know them on a personal level, I found most to be hard-working and decent," says Akins, who received his Ph.D. in anthropology from UF in 1998 and is now a visiting assistant professor at the University of North Florida. "They simply got caught up in cultural changes that were beyond their ability to understand, and in a desperate search for answers, bought into the movement's conspiracy theories."

Ironically, it was a life-changing event in the U.S. Army that led to Akins' academic sojourn through the dark world of the militia.

After a year of college in the early 1980s, Akins enlisted in the Army and embarked on what appeared to be a successful military career. After several years, he landed an assignment with the Army's elite "Old Guard," which serves as a mounted escort for presidential functions.

But in 1989 his career was cut short in a stable in Arlington, Virginia, when several of the unit's horses stampeded and trampled him. After a long and painful rehabilitation from a broken back, neck and ribs and a shattered knee, Akins received a medical discharge and returned to college, earning a bachelor's degree in education from Florida State University and a master's in anthropology from UF.

Life had prepared Akins well for his dissertation research. A deeply religious Southern Baptist with military experience and skill with firearms, he could converse easily on subjects valued by the militia movement. A few discreet inquiries at area gun stores soon led to an invitation to attend a meeting in Jacksonville of the North Florida Militia. From that meeting, and dozens of others like it over the next three years, as well as participation in combat exercises and other functions, and a careful study of Militia Movement literature, Akins began to understand the militia mindset.

Ideological Octopus

Akins traces the birth of the modern Militia Movement to a gathering of right-wing activists in Colorado in October 1992 that has become known as the "Rocky Mountain Rendezvous." There, white separatists, neo-Nazis, tax protestors, Ku Klux Klan members and others synthesized scores of complaints about the government into a conspiracy theory which explained many, if not all, of the "problems" of contemporary American culture.

"This theory is like an 'ideological octopus,'" Akins says. "Each tentacle represents a specific concern, such as firearm ownership, abortion or prayer in public schools."

The tentacles draw activists on these various issues toward the octopus' body, the entities the Militia Movement blames for all problems: the U.S. government and the United Nations, the so-called New World Order.

"Economic changes are the result of an international banking conspiracy," Akins says. "Financial and military support for Israel is redistributed to America's enemies. Environmental laws limit the free and 'wise' use of America's resources and create dependency on international corporations. Abortion is government-funded population control. United Nations peacekeeping operations subvert the U.S. military by incorporating them into a New World Order police force. Guns are confiscated so citizens cannot protect themselves."

Many people in this country are concerned about the very issues the Militia Movement preaches, Akins says, but few would ever consider joining a militia.

"What are the factors that separate those who buy into this conspiracy theory from those who laugh at it?" he asks. "What separates those who will attend meetings from those who will not? Among those who attend, what separates those who will join from those who will never return?"

Based on his observations, Akins says the people most likely to embrace the militia conspiracy theory seem to be disaffected or resentful native-born American citizens who are suffering economically and have come to associate the federal government with both their personal problems and with the larger problems in society.

But it takes more than a dissatisfaction with society to push a reasonable person into the Militia Movement.

Akins says his research indicates that the primary factor leading to a person's acceptance or rejection of militia ideology is the presence of a fundamentalist worldview. Potential recruits invited to meetings are far more likely to accept the militia conspiracy theory as valid if they have a fundamentalist perspective at the time of their exposure, he says.

"Although some people have always suffered economically and some Americans have always distrusted the federal government, there has not always been such a large segment of the population that is inclined to interpret its reality through a fundamentalist perspective," Akins says. "The Militia Movement can be seen as just another example of the rising tide of fundamentalism that has swept the world in the past two decades."

Militia For The Millennium

The final key to understanding the Militia Movement is timing. Why did the Militia Movement develop now? Akins cites six historical events.

The initial groundwork was laid by the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Gulf War, the election of President Bill Clinton and the approaching end of the 20th century.

The Gulf War was important for three reasons, Akins says. First, it was fought under the auspices of the United Nations, with American troops and money subordinated to the command and for the benefit of foreigners. Second, former President George Bush repeatedly referred to the "New World Order" being constructed by the United Nations. Finally, the government's treatment of American veterans suffering "Gulf War Syndrome" enraged many patriots.

Bill Clinton's detractors consider his election in 1992 with fewer than 50 percent of the votes a victory for sexual degenerates, minorities, the "intellectual elite" and "East Coast liberals," Akins says. Indeed, Clinton has become a symbol for everything right-wing factions in America oppose.

Finally, what could encourage a millennial movement more than the end of a millennium? A 1994 poll conducted by U.S. News & World Report found 61 percent of Americans believed Jesus Christ will return, 44 percent believed that there will be a final battle of Armageddon and 49 percent believed there will be an Antichrist. Of the 61 percent who believed Jesus will return, almost half believed this will occur at or near the end of this century.

These four events were capped by the incidents at Ruby Ridge, Idaho, and Waco, Texas, Akins says. Ruby Ridge, where FBI sharpshooters killed the wife and son of white separatist Randy Weaver, went unnoticed by most Americans. But the burning of the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas, was broadcast live into living rooms nationwide. For people in economic crisis, focusing their attention on government mismanagement and corruption, and interpreting their observations through a fundamentalist worldview, Akins says, the message was clear: Step out of line and Uncle Sam will kill you.

Revelations

Through his observations, interviews and a careful reading of militia literature, Akins has been able to paint a vivid demographic picture of militia members in general and Florida militia in particular.

His study defies the common belief that members of violent extremist groups are uneducated and poor. He found that, statistically, militia members are better educated than the general population and their membership cuts across traditional class boundaries.

Census data show about 27 percent of American adults are high school dropouts, compared with less than 10 percent of militia members throughout Florida, as Akins' study found.

"There are faculty members, business owners, corporate executives, lawyers and doctors intermingled with rednecks, the unemployed and menial labor," he says.

An estimated 440 militia groups exist nationwide, with Florida having one of the largest concentrations of them and white supremacy groups, Akins says. He identified 77 militias in the state, ranging in size from five to 30 members, along with 21 Ku Klux Klan and eight Nazi or skinhead groups.

"I found that nearly everyone in the militia groups owns multiple firearms, at least one member owns automatic assault weapons and the amount of explosives each organization has access to is far beyond what most people could imagine," Akins says. "They also have a lot more ties to violent groups in Europe and Australia than most people think, using the Internet to exchange information about how to make weapons and manufacture explosives."

Despite their violent rhetoric, Akins says, most members are active in their church, some are local politicians and nearly all are married with children.

His dissertation complete, the last artifact of his time with the militia is a vivid tattoo on his forearm. Akins says someday he'll have the Confederate flag and the Latin words Odi et Amo (hate and love) removed.

Although his comrades may have expected a more favorable portrayal of their crusade than they ultimately received from Akins, they could not accuse him of "infiltrating" the movement. In accordance with anthropology ethics, he fully disclosed to the various militia groups that his time with them was for research purposes. But he admits he has taken "appropriate precautions" in case some of them feel betrayed.

Sociology Student Finds Anti-Racist Groups Growing

While the Militia Movement that Keith Akins chronicled may get most of the publicity, another UF student's doctoral dissertation has found that radical, mostly white anti-racist groups have more than doubled in number during the 1990s but have been largely overlooked by the media.

Sociology doctoral candidate Eileen O'Brien found more than 300 groups with predominantly white memberships have been formed to counter the growing visibility of skinheads, the Ku Klux Klan and other racist organizations. She interviewed anti-racist group leaders in the South, Midwest and Northeast for the study.

One of these group's heroes is John Brown, a white who was executed for attempting to ignite a revolt against slavery. Brown, an ardent abolitionist, led an 1859 raid on the arsenal at Harpers Ferry, W.Va., in hopes of touching off a slave rebellion.

One group, the New Abolitionists, with chapters around the nation, wants to boost Brown's visibility with marches, picnics and graveside remembrances during the first week of May, O'Brien said.

"Blacks have celebrated Brown's birthday for more than a century, but now some whites are beginning to get involved and honor his memory," she says.

O'Brien, who went to the groups' workshops and accompanied members to Ku Klux Klan protests, said she was interested in researching specifically how whites get involved in protesting racism.

"There has been a long and silent history of whites who have been anti-racist," she says. "The Underground Railroad couldn't have existed without whites."

Joe Feagin, a UF sociology professor and national expert on race relations who supervised O'Brien's research, says the subject has been largely ignored by scholars.

"There has been virtually no research on whites involved in anti-racist movements, particularly since the '60s, even though currently there are 300 such groups," he said. "But there must be a thousand articles on the growth of racist groups."

The two organizations O'Brien studied were Anti-Racist Action, which engages in social issues, and the People's Institute for Survival and Beyond, a training group that offers workshops to social workers and community leaders.

Anti-Racist Action, which began protesting neo-Nazi and Klan activities, has more than 70 chapters in the United States and 20 in Canada and distributes a newsletter to about 25,000 people, O'Brien says.

More than 18,000 people have participated in workshops offered by the New Orleans-based People's Institute for Survival and Beyond, which focuses on more subtle aspects of racism, she says.

"By 2060, the population of people of color is going to double and whites in this country will be a minority," O'Brien says. "These groups are likely to continue to grow as whites struggle with how to deal with the despair and guilt over how they have treated blacks in the past and learn how to live differently in the future."