Agriculture

Without Soil Offers New Alternatives For Florida Farmers

Agriculture

Without Soil Offers New Alternatives For Florida Farmers

By Michael Podolsky

Like a plant from H.G Wells’ Food of the Gods, the 30-foot-long tomato vine hangs suspended from the greenhouse roof, heavy with bright red fruit.

The enormous plant isn’t even rooted in the earth; it grows instead from a bag of sterile volcanic rock called perlite. The plant draws its nourishment from a carefully measured cocktail of elements and minerals that drips into the bags of perlite like a hospital IV.

Welcome to the future of agriculture — and at the University of Florida, the future means fresh tomatoes, strawberries and

other

fruits and vegetables almost year round.

other

fruits and vegetables almost year round.

Researchers at the UF’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences have been working on the growing technique known as hydroponics since the late 1980s.

Hydroponics is defined as agriculture that uses a growing medium other than soil, says Bob Hochmuth, an extension agent at UF’s North Florida Research and Education Center (NFREC) — Suwannee in Live Oak. Hochmuth and his brother, George, who is the director at NFREC in Quincy, have spent years perfecting hydroponic agriculture and promoting it with farmers around the state.

"We’ve got about 75 acres of crops in the state that are being grown

hydroponically," Bob Hochmuth says. "We’ve been working here to support

those farmers who choose to use this technique."

Hillsborough County extension agent Eric Waldo examines strawberries being grown hydroponically at UF's Gulf Coast Research and Education Center in Dover. Waldo says the strawberries were "very similar" in taste to traditionally grown berries. |

Hydroponic agriculture is a labor- and equipment-intensive venture, Bob Hochmuth says, but the crop yields are astonishing compared to traditional agriculture. "The advantages of growing hydroponically are many," he says. "For tomatoes, for example, you can harvest crops just about year round. Instead of two three-week picking seasons, you’re looking at a sustained crop yield for about eight months out of the year." Hochmuth says an average acre of traditionally farmed land will earn a farmer between $20,000 and $30,000 per year. An average acre of hydroponically grown crops will earn between $200,000 and $250,000 per year. "Of course, your costs are initially much, much higher for hydroponics," Hochmuth says, citing expenses to maintain greenhouses and higher labor costs. "But you are talking about year-round harvesting." Because of the higher costs of growing hydroponic crops, farmers who

use the technique tend to plant more valuable crops, such as cucumbers,

tomatoes and strawberries. Hochmuth says these crops are highly sought

after by consumers so farmers charge a premium for them.

|

"We are concentrating on the crops that we feel have the greatest feasibility of bringing the highest value per acre — strawberries fit that bill. And there are crops that just can’t be grown traditionally in Florida that can be grown using hydroponics," he says, citing European Burpless Cucumbers as an example. And who could resist a pint of fresh strawberries in the middle of winter or a head of lettuce that had never touched the ground?

Hochmuth says that of the 75 acres now being grown hydroponically in Florida, the top crops, in order, are colored bell peppers, tomatoes, cucumbers and lettuce. Strawberries are also a crop that has been successfully grown hydroponically.

In Florida, 6,000 acres of farmland are devoted to strawberries. Valued at some $100 million annually, they trail only tomatoes, peppers and potatoes among Florida agricultural products. It is toward strawberries that most of UF’s hydroponic research is geared.

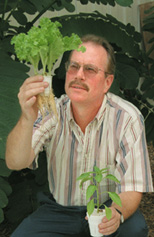

Education Agent Bob Hochmuth checks bell peppers being grown hydroponically at UF's Suwannee Valley Research and Education Center in Live Oak. Peppers are the leading hydroponically grown crop in Florida. |

Critical to hydroponic growing is perlite, a volcanic rock mined in Greece and in the Southwestern United States. It is crushed to the consistency of kitty litter, then heated, which makes it expand. Perlite has a high water-holding capability and aerates the roots well. The black bags in which it is placed minimize the amount of sunlight that reaches the roots. Another key to successful hydroponic agriculture is the plant diet. George Hochmuth has concentrated much of his research on creating the ideal nutrient solution for hydroponically grown plants. Plants must have varying combinations of 16 key elements to survive.

While air and water supply carbon, oxygen and hydrogen, fertilizers supply

phosphorus, potassium, nitrogen, sulfur, calcium, iron, magnesium, molybdenum

and chlorine. As plants grow, they need differing amounts of these elements

— for example, if a plant receives too much nitrogen early in its life,

it will tend to grow too quickly, which distorts leaves and stems, causing

cracks which allow rot to get into the plant, according to George Hochmuth’s

research.

|

Nutrient needs can differ from farm to farm, depending on the composition of the water supply. But once a farmer knows the mineral content of the well water used for irrigation, adjusting the nutrient recipe is a relatively simple task.

While hydroponics may seem like the stuff of science fiction, changes in environmental laws may soon make it a more viable option to farmers faced with losing one of their most effective soil pesticides.

Concerned about its effect on the Earth’s protective ozone layer, the

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has enacted rules that will phase

out the use of methyl bromide over the next five years. Methyl bromide

is a soil fumigant that addresses the four biggest causes of crop damage

— insects, nematodes, diseases and weeds.

"We’ve used methyl bromide very extensively in Florida," Bob Hochmuth says. "It’s been very effective in helping crops like tomatoes, strawberries and peppers. But by the year 2005, it will be completely phased out and sooner than that its price will be so high that it will not be cost effective." Faced with the loss of methyl bromide, "it makes sense to move production of some high-value crops out of the soil altogether," he says. While hydroponic growing offers farmers an alternative to pesticides, the initial costs of greenhouse construction are prohibitive, so IFAS researchers are looking for ways to bring those costs down, primarily by moving hydroponic growing outdoors. In tests at UF’s Gulf Coast Research and Education Center in Dover, Hillsborough Extension Agent Eric Waldo and horticulturist John Duval are conducting a research and demonstration project to measure how strawberries grow outdoors in bags filled with perlite and other inorganic growing media. |

Seminole County Extension Agent Richard Tyson examines lettuce being grown hydroponically. |

"With our crop from last year, we had a similar yield to crops grown

indoors," Waldo says. "Being able to grow hydroponically out of doors is

very significant because it eliminates the very high price of building

and maintaining greenhouses."

|

The costs are still high for out-of-doors hydroponics, Waldo says, but his research shows that, eventually, economy of scale can bring the overall price down, especially since replacements for methyl bromide are expected to be significantly more expensive. "Some of the replacement fumigants can be up to 10 times more expensive than methyl bromide," Waldo says. "If farmers are looking at spending that kind of money, they may consider making the investment in hydroponic systems." Waldo says his hydroponically grown strawberries were "very similar" in taste to both traditionally grown and indoor-hydroponically grown berries. |

"We did some sugar tests, and the results indicated no real difference in the fruit," he says. "The big difference was that the test crop fruited a few weeks before the control crops."

Earlier harvest translates into a marketplace advantage as consumers are apt to pay higher prices for the first strawberries of the season.

Marvin Brown, president of BBI Produce Inc. in Dover, the state’s largest grower and shipper of fresh strawberries, said soilless strawberry production — although still in its infancy — could be a part of his future.

"With the rapidly approaching deadline for discontinuing use of methyl bromide as a soil fumigant and no viable replacement in sight, soilless alternatives deserve serious attention," Brown says. "Advancements in technology and growing techniques will undoubtedly increase our desire and ability to use alternative production methods that are both economical and ecologically acceptable to all."

In North Florida, Bob Hochmuth also conducted trials of outdoor hydroponically grown strawberries with excellent results. Those hydroponic plants produced twice the fruit found on soil-bound strawberry plants.

|

In this cross section of a plant being grown hydroponically,

an irrigation tube supplies a nutrient solution to the plant, which is

anchored in a plastic containment bag containing perlite, a volcanic rock

that has high water-holding capability and aerates the roots well. In some

hydroponic systems, excess nutrient solution is returned to a collection

chamber. The nutrients are replenished, and the solution is recycled back

through the system.

|

"Traditionally, you’ve got to have about 4 feet between rows," Waldo

says. "With hydroponics, that distance is much smaller and you can fit

many more plants into the same space."

| George J. Hochmuth II

Professor and Center Director North Florida Research and Education Center — Quincy (352) 392-2134 gjh@gnv.ifas.ufl.edu |

Robert C. Hochmuth

Extension Agent North Florida Research and Education Center — Suwannee (904) 362-1725 bobhoch@ufl.edu |

http://liveoak.ifas.ufl.edu/gh_&_hydroponics.htm