|

||||||||||||||||

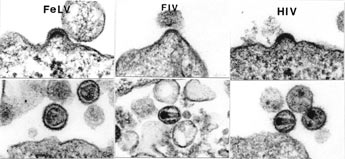

| Cats. The Egyptians worshipped them. T.S. Eliot immortalized them, and Andrew Lloyd Webber sent them to Broadway. Now UF researcher Janet K. Yamamoto is saving their lives with her groundbreaking research on feline immunodeficiency diseases — research that may also lead to an AIDS vaccine for humans. by Patricia Bates McGhee A pathobiology professor in UF’s College of Veterinary Medicine, Yamamoto is a hero among cat lovers. She not only co-discovered the deadly feline immunodeficiency virus, or FIV, but she also developed the first FIV vaccine. According to the American Association of Feline Practitioners, up to one in 12 cats may test positive for FIV. The virus is transmitted from one cat to another primarily through bite wounds caused by fighting. Unlike HIV, it’s spread in high levels through saliva. But like the human form of the virus, FIV can be deadly for cats because it weakens the animal’s immune system so that it is no longer able to fight off infection or other diseases. “No cat-to-human transmission has ever been reported in the literature,” Yamamoto says. “We do, however, see the virus spreading rapidly through the cat population, with up to 15 percent of at-risk or sick cats already infected with FIV.” FIV is most common among cats that are exposed to the outdoors and in multiple cat households. Yamamoto has spent much of her career studying FIV and ways to combat it. In 1985 she established the Laboratory of Comparative Immunology and Retrovirology (LCIR) at the University of California, Davis. It was in that lab that she and colleague Niels Pedersen co-discovered FIV in 1986 by isolating the virus from two healthy, disease-free — or specific-pathogen-free (SPF) — cats injected with blood from infected clinical cats. In 1987 their findings were published in the journal Science. In 1993, with encouragement from her University of Texas Medical Branch mentor Howard Johnson, who was by then a graduate research professor in the UF Institute of Food and Agricultural Science’s Department of Microbiology and Cell Science, Yamamoto moved to UF and brought the LCIR with her. Today it is housed in UF’s Veterinary Academic Building. Since the discovery of FIV in 1986, LCIR has been working to determine the relevance of the FIV model to human AIDS. Both are lentiviruses, which characteristically remain in the host for a long time, causing a slow progression toward death. The lentivirus is spherical and about 1/10,000th of a millimeter in diameter. It contains only 9,749 nucleotides, making it a comparatively small virus compared to a human cell (which has up to 3.5 billion nucleotides) and to other viruses. Its dominant feature is that it is enveloped with a truncated cone-shaped core inside that Yamamoto says “looks like an ice cream cone.” FIV in domestic cats most likely originated with African lions, much like HIV-2 may have originated from simian immunodeficiency virus, or SIV, in African monkeys. Like SIV in monkeys, FIV lentiviruses do not cause disease in African cats. The LCIR has a relatively brief but impressive history of studies on comparative retrovirology, the study of retroviruses like the lentivirus. A retrovirus is a fairly simple virus that contains RNA rather than DNA as its genetic material. The RNA of the virus is translated into DNA, which inserts itself into an infected cell’s own DNA. Retroviruses can cause many diseases, including some cancers and AIDS. Initial funding for the LCIR was solely obtained from national and academic sources, such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH), intramural, and foundation grants, for studying the origin and development of the feline leukemia virus and, later, FIV. It was FIV’s discovery that shifted the emphasis of research toward the development of FIV as a small-animal model for AIDS. Yamamoto says crossing over to human disease study opened up new sources of funding, particularly from the NIH, which is currently funding a five-year, $1.2 million project in Yamamoto’s lab. “Medical colleges tend to attract many more research dollars than veterinary colleges,” says Yamamoto. “Our (LCIR’s) strong affiliation with the veterinary college has provided us a rare opportunity for federally funded research to have an impact on veterinary medicine.”

FIV and HIV––Similar but Different Researchers in Yamamoto’s lab focus their attention on cats with FIV who take a long time to exhibit symptoms of the disease. Yamamoto and her colleagues believe these so-called “long-term non progressors” may provide clues to preventing or curing the disease in both cats and humans. One of the LCIR’s major interests is in the use of the FIV vaccine model to identify effective HIV vaccine designs. The FIV model has several advantages for such studies: Genetic analyses show that FIV has five main subtypes, thereby allowing for vaccine studies on subtype challenges from different species. The

use of cats is less hazardous and less expensive than most other models. FIV

causes a naturally occurring infection in cats that is clinically similar

to HIV in origin and development.

An Ounce of Prevention UF licensed the FIV vaccine, called Fel-O-Vax FIV®, to Kansas-based Fort Dodge Animal Health (FDAH), a division of the New Jersey-based pharmaceutical company Wyeth, in July 2002. Available through licensed practicing veterinarians nationwide, the vaccine is the culmination of 14 years of work by LCIR and FDAH and is based on Yamamoto’s patented technology. UF and UC Davis hold joint patents on the FIV vaccine, and FDAH, with USDA approval, used their research to develop the commercial vaccine. Steve Chu, Fort Dodge’s senior vice president for global research and development, called Yamamoto’s vaccine technology “a scientific breakthrough for lentivirus vaccine and disease prevention.” Fel-O-Vax FIV®, which has an 84-percent efficacy rate, requires three initial doses and then one yearly thereafter. The vaccine is recommended as an aid in the prevention of infection with FIV and can be administered to cats as young as 8 weeks old. It provides protection for a minimum of 12 months. “The studies that resulted in the development of the FIV vaccine are the product of a unique cooperative interaction between academia, industry and federal agencies,” Yamamoto says. “It is critical that further studies of our vaccine take place on an international level to assess whether protection against worldwide strains of feline AIDS is possible, and whether vaccines composed of viruses from these long-term nonprogressor cats are effective.” “Formal approval of the vaccine is really a tribute to Dr. Yamamoto, who doggedly persisted in pioneering this approach for an FIV vaccine,” says her colleague and co-discoverer, Pedersen. Two wall hangings in Yamamoto’s UF office sum up her passions for science and cats. One is a black-and-white photograph from 1950 of her father shaking hands with Albert Einstein. Her family first met Einstein in the 1920s when her grandfather, a publisher in Japan, invited the famed physicist on a speaking tour of Japan. Her father, who was one of the first Japanese invited to the United States after World War II, was also a publisher and was responsible for having the works of Einstein and Pearl S. Buck translated into Japanese. Across from the photograph is a simple black-and-white line drawing of a healthy, relaxed tabby. Yamamoto’s research life revolves around her lab cats, and her home life revolves around her companion cats. All eight of her home cats are former subjects in her research, including a 12-year-old mother cat named Mommy, who had a bone-marrow transplant, and two of her daughters, Cici and Booty, who are 7 years old. “I do research only for the good of the cat and quality of life for the cat so that this research will, in the long run, benefit the quality of life for all cats,” she stresses. “Cats contract life-threatening and terminal diseases. I use cat models to research these diseases and ultimately prevent them in cats and improve their quality of life. I research what is real for cats.” Kind, sincere words spoken by cats’ best friend and hero. Janet

K. Yamamoto

• FIV causes feline AIDS, a silent, deadly disease that attacks a cat’s immune system but is not the same as the human AIDS virus. • According to the American Association of Feline Practitioners, up to one in 12 cats tests positive for FIV. • With a compromised immune system, the cat is no longer able to fight subsequent infections or disease. • Any cat with exposure to the outdoors is at risk for FIV. • FIV is mainly transmitted during cat fights via bite wounds. • Initial, or first-stage, symptoms include loss of appetite, fever, lethargy, diarrhea, swollen lymph nodes and low white blood cell count. Cats infected with FIV start to become listless, do not groom themselves properly and are prone to secondary infections. •

Second-stage cats may recover and show no symptoms yet become • Third-stage cats experience weight loss, sores in and around the mouth, poor coat and secondary infections, which become more frequent and resistant to treatment. FIV Prevention Tips • Limit exposure of indoor cats to outdoor cats • Use caution when introducing a new cat to a multi-cat household • Test a new cat (especially a stray) for FIV prior to joining the household • Isolate an aggressive cat from other cats • Vaccinate to prevent the disease |

||||||||||||||||

|